![]()

Paul Rand said, “Visual communications of any kind… should be seen as the embodiment of form and function: the integration of the beautiful and the useful.” It’s not only about how it looks, or how it works, but about how it looks and works together. Whether you’re a student or a practicing designer, it’s helpful to occasionally look back at the work of iconic designers like Rand. I wrote Graphic Icons: Visionaries Who Shaped Modern Graphic Design to highlight pioneers of graphic design, from El Lissitzky to Paula Scher. Each of these figures offers inspiration and lessons for all designers. Here are a few that contributed to the rise of corporate identity design:

Lester Beall

1903–1969

Lester Beall became the first American graphic designer to successfully integrate the European avant-garde into corporate America, and he did it through his designs of posters, magazines, packaging, and identities. As part of the U.S.’s New Deal, Beall designed a successful campaign of posters to support the Rural Electrification Administration’s efforts to bring power to rural residents. The posters were simple and graphic, with flat illustrations, to appeal to an audience with little education.

Moving from Chicago to New York in 1935 brought Beall new opportunities. Corporate identity design — an entire visual language for a company, with detailed guidelines on how to use it — is now a well-established discipline, but back then, it was not. Beall designed strong graphic identities and extensive usage guidelines for companies like Connecticut General Life Insurance and Caterpillar Tractors. His work for International Paper set forth guidelines on usage for everything — including correspondence, delivery vehicles, building signs, and packaging.

Erik Nitsche

1908–1998

In 1955, defense industry contractor General Dynamics wished to be seen as an agent of peace, rather than of weapons and war. Executives gave Swiss-born Erik Nitsche complete control to create a comprehensive new identity designed to shift public opinion and shape the company’s image. Though it wasn’t a big logo project, it proved to be a case study in innovative corporate design. Since much of the company’s work, like the first atomic submarine, was top secret, Nitsche used abstract symbols to express the concept of using military technology for peaceful ends. He designed a series of posters to represent the company at Geneva’s International Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy (dubbed the “Atoms for Peace” conference).

He combined vivid colours and geometric forms with scientific imagery to develop designs that were bright and optimistic (two words that also describe Nitsche personally). It was a new way to present scientific information, and its influence can be seen in the space-age design style of the late 1950s.

To document the company’s history, Nitsche designed Dynamic America: A History of General Dynamics Corporation and Its Predecessor Companies, a 420-page book packed with visuals. It raised the bar for nonfiction book design, and still inspires designers today.

Paul Rand

1914–1996

Paul Rand mastered design for advertising, magazines, and books, but he made his biggest mark in the area of corporate identity. One of his most famous logos was for IBM — a project that began as a collaboration with architect Eliot Noyes in 1956 and unfolded over more than 20 years. Rand knew the conservative company needed to be guided through a design progression. His first step was to tweak IBM’s existing slab serif typeface, but it wasn’t until 1972 that he incorporated the still-familiar horizontal stripes to better unify the three letters. In addition to the logo, he designed IBM’s packaging, marketing materials, and annual reports. Rand was responsible for some of corporate America’s most recognisable logos including Westinghouse, ABC, and United Parcel Service.

Design wasn’t Rand’s only talent. Perhaps more important: his skill in convincing corporate executives that design has value, and that it should evolve as companies grow and develop.

Ivan Chermayeff and Tom Geismar

Chermayeff: 1932– ; Geismar: 1931–

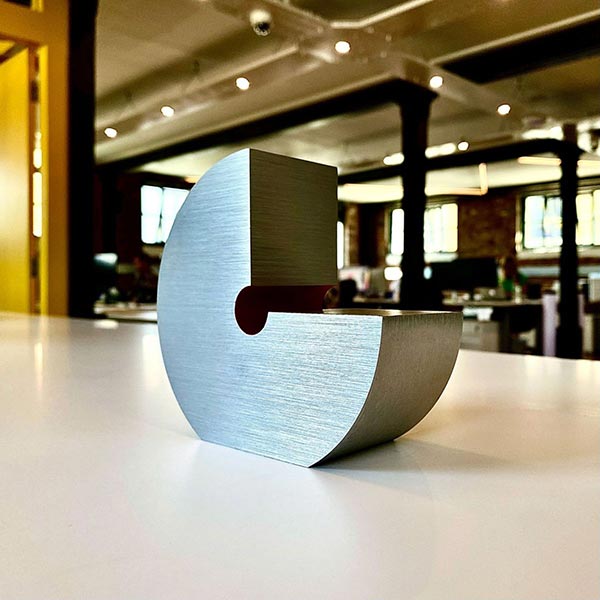

In 1960, Chermayeff and Geismar proposed a radical idea: a corporate logo, for Chase Manhattan Bank, that was not based on letterforms or a recognisable image. Their design was simple — four wedges rotated around a square to form an octagon — but it met with resistance, because at that time no major American corporation had an abstract logo. And that’s precisely why Chermayeff and Geismar’s design worked; it stood out from the competition and became an identifying symbol inextricably associated with Chase. Soon, other corporations followed suit with abstract logos of their own.

But Chermayeff and Geismar haven’t limited themselves to a particular style. For them, design is solving problems, and they pursue the best solution, regardless of form. They’ve designed more than 100 corporate identities, for clients such as PBS, Barneys New York, and Pan Am. For Mobil Oil, Chermayeff and Geismar created a simple logo of geometric type to echo the circles and cylinders of the gas station designs. Thanks to a simple gesture — the setting of the “o” in red — the Mobil logo has remained iconic.

More than 50 years after its start, the firm is still going strong; partner Sagi Haviv has joined the masthead, and the firm is now called Chermayeff & Geismar & Haviv. And they continue solving problems.

Walter Landor

1913–1995

Walter Landor didn’t think of design as art. It was communication. He constantly sought ways to better understand his audience by testing package designs right on grocery-store shelves and asking shoppers directly for their opinions. He pioneered design based on consumer research — and built Landor Associates, one of the world’s most successful branding agencies as a result.

The days of store clerks recommending products had passed — he knew that the package itself must send the message through strong shelf impact. Seeking emotional connections between brands and consumers, Landor preferred warmer, more accessible designs over the cooler Swiss modernism that was popular at the time. Brands as diverse as Levi’s, Coca-Cola, Bank of America, Alitalia, and the World Wildlife Fund benefited from Walter Landor’s expertise, and his legacy of research and strategy lives on.

Michael Bierut

1957–

“I admire creative people who don’t wait for inspiration or strokes of genius, but who can simply show up for work every day and do the best they can,” says Michael Bierut, a partner at the New York office of Pentagram.

Bierut excels as an identity designer, developing comprehensive brands from the ground up as well as consulting with companies that need a refreshed look. For avant-garde performance space Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM), Bierut developed a simple yet bold visual language of large cropped type, suggesting something exciting beyond the horizon. The identity remains one of the most recognisable in New York City.

Luxury retailer Saks Fifth Avenue had used several logos over the years and wanted something new. Bierut looked back through the brand’s history and found a cursive logo from 1973, drawn by Tom Carnase (and part of an earlier identity designed by his old boss, Massimo Vignelli). To freshen it up, Bierut placed the logo into a square, then broke that square into several smaller squares that could be rotated and arranged to create hundreds of different patterns. The ever-changing new look references the store’s long heritage, while looking fresh and modern.

—

Excerpted with permission from Peachpit Press.

John Clifford is the author of Graphic Icons: Visionaries Who Shaped Modern Graphic Design, and was the creative director of the late NYC design firm Think Studio, with a focus on identity, digital, publishing, and print design.

Get Graphic Icons from:

There’s another excerpt on davidairey.com, too, featuring Jan Tschichold.

Comments

paul rand is one of my favorites.

i loved his era of logo designing because logos were also simple & clean without gradients or effects.

Ronald, I agree–I love simple & clean. David, thanks for the opportunity to write for your great site!

Nothing against these designers, they are all obviously great. But I keep seeing odes to the same basic group over and over again. Were there no inspiring early designers of color? Or women?

Well played John! I appreciate the homage to the greats. Nice comprehensive post, thanks for taking the time.

> v <

Trish, great point. The key word is “early”–not many. If we were talking about contemporary designers, we’d obviously have more women and people of color. There are some, though: Georg Olden was a pioneering African American broadcast designer, who did great work for CBS and went on into advertising. Read more here: http://blackcreatives.com/tools-and-resources/2014/2/18/celebrating-creative-contributions-graphic-icons-by-mikaela.html

And Cipe Pineles was the first female art director of a major US magazine, and the first female member of the Art Directors Club. Learn more about her at Graphic Birdwatching: http://www.graphicbirdwatching.com/article/cipe-pineles/

The – after the birth year in living people, just isn’t right.

Great designers but where is Saul Bass?

Thanks, Vincent–glad you like it. Paz, this post is an edited excerpt from the book Graphic Icons. Saul Bass, and many others, are in the book.

It’s a pleasure to host you, John. Well done with the book.

Trish, I watched a good documentary a while back by multimillionaire businesswoman Hilary Devey, titled Women at the Top. Two of the main outcomes were that businesses with a roughly 50/50 boardroom split between men and women perform better than their rivals, making the strongest business case against sexism, but that the main reason why more men take the top jobs is probably because of pregnancy, with women torn between work and looking after children. Granted, Hilary owns a haulage firm so the split is likely to be more exaggerated for her than within design firms, but it’d make a good post on its own. Maybe I’ll ask around for opinions.

I am very proud to say my father, Arthur Boden, was the first designer/illustrator Paul Rand hired for IBM’s legendary in-house design department in the late 1950s. He worked as art director for IBM for 17 years, with many successful years to follow as a freelance designer. He turns 91 this year, and although much diminished, loves to talk about his IBM design days and tons of stories about Paul Rand and IBM. I am cataloging and digitally archiving my fathers massive and stellar design work, his paintings, illustrations, sketches and sculpture.